Part Seven: ELECTION LAW — Election Debate

Election debate is the final entry in a series on election law. Today is a real-world, historical perspective on the presidential election. Whatever the result this Tuesday — and you should vote — keep in mind the grander electoral scheme of which you are a part. Election debate. 2020.

So bring on blog post, part seven, with this and other posts raising issues worth considering in advance of the upcoming Presidential election.

A MATTER OF INTERPRETATION

In the presidential election scheme, we know a few truths for 2020. The vote will be close. Two-party politics dominate. An independent/splinter candidate has no real shot at electoral success.

Is this really what the framers envisioned in 1787 when drafting the Constitution of the United States?

Doubtful.

Not only was the Electoral College system problematic almost from the moment it left the starting block, but the presidential election process has grown more complicated, more winner-takes-all, and more divisive than perhaps the delegates would have imagined.

DIVISION WITHIN

It didn’t take long. The delegates knew early on that their system of government had become divisive.

Travel back to 1797. Ten year after the Constitution was drafted. At a time when Thomas Jefferson was serving as Vice President. Jefferson wrote a letter to his colleague, Edward Rutledge, reporting the divisive mood at the nation’s capital:

“The passions are too high at present, to be cooled in our day. You & I have formerly seen warm debates and high political passions. But gentlemen of different politics would then speak to each other, & separate the business of the Senate from that of society. It is not so now. Men who have been intimate all their lives, cross the streets to avoid meeting, & turn their heads another way, lest they should be obliged to touch their hats. This may do for young men with whom passion is enjoyment. But it is afflicting to peacable minds. Tranquility is the old man’s milk.”

(Jefferson to Rutledge, June 24, 1797, in Jefferson, Papers, 29:456-57.)

Less than a decade after ratifying the Constitution you had political opponents, who knew each other all their lives, cross the street and turn then head to avoid meeting or acknowledging one another.

HIS FRAUDULENCY

If Jefferson’s report, from 1797, sounds familiar to today’s presidential politicking, here are a few more.

In the election of 1824, the Congressional caucus nominated Albert Gallatin for Vice-President. The caucus was attacked as undemocratic and Gallatin, the nominee, later withdrew his candidacy.

The claims in that election, just as today, related to attacks on credibility, a candidate’s “fitness” for office, and the failure to obtain popular support.

Need more proof? Fifty years later, when Rutherford B. Hayes won the electoral vote, not popular vote in the election of 1876, many in the losing party referred to him as “Rutherfraud” B. Hayes or “His Fraudulency” during his 4-year term.

Unlike fine wine, the divide did not get better with time.

Now sitting over 100 years removed from Hayes, over 150-years removed from Gallatin, and over 200 years from Jefferson, the same familiar themes persist, with candidates, and parties, in a gridlock of attacks, issue-related and personal, that, if not on par with past history, certainly have historical precedent.

The point being that for those who argue this election cycle is the worst of all time, historical review suggests this election cycle is not far removed from the ilk of elections-past.

THE CONSTITUTIONAL FABRIC

Prior blog-posts attempted to bring the political-divide within the context of the Constitution of the United States.

Much of the authority and background can be found in Ray Raphael’s book Mr. President: How and Why the Founders Created a Chief Executive (2012). There, Mr. Raphael sums up the Constitutional Law debate that has morphed into countless laws, opinions, cases and legal jurisprudence that makes a horse run:

“The document the framers created was not some algorithm that could be dutifully followed to achieve optimum results. Instead, by necessity, it would have to be treated as an incomplete and therefor evolving guide that pointed in a general direction but left more room than some might prefer for interpretation–and, like it or not, discretion.”

Taken one step further, the interpretive and discretionary application of the Constitution forms the center-piece to the very-political fabric that holds court today, just as it did 200 years ago.

Just this week, a Supreme Court Justice (Gorsuch) described the democratic process as both frustrating but necessary:

“[W]hat sometimes seems like a fault in the constitutional design was a feature to the framers, a means of ensuring that any changes to the status quo will not be made hastily, without careful deliberation, extensive consultation, and social consensus. … Nor may we undo this arrangement just because we might be frustrated. Our oath to uphold the Constitution is tested by hard times, not easy ones.”

(Democratic National Committee v. Wisconsin State Legislature, 592 U.S. ____ (2020)).

HOW WE GOT HERE

The point is there is process. Deliberation and compromise are built into the Constitution. Disagreement exists within the Constitutional scheme. And this scheme is not to be thrown to the wind simply because of one-person’s desire to throw it there.

Indeed, our system of government does not require (or even want) you to check opinions at the door come election time.

Instead, the American-way, and in particular the right to vote, is to take on the weighty obligation of voting while fully embracing the views of others and your own positive and negative personal opinions.

The framers themselves were not in agreement with everything in the Constitution — nor would you be expected to be in agreement with all positions or all sides when exercising your right to vote.

This is how it was in 1787.

This election cycle is no different.

ELECTION 2020

Which leads to a final point. This series was largely composed four years ago. That election pitted a perceived wildcard (Trump) versus the establishment (Clinton). You know the result.

Yet when I looked back at notes from then, the theme there was apathy. Voter turnout, while strong, was not what was expected — particularly in certain parts of Wisconsin.

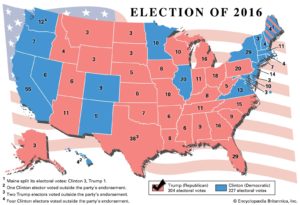

It made for an interesting election. On the eve of 2016 election, of the 11 targeted states, Trump had a clear lead in only two, Ohio and Iowa. But when polls closed, “swing states” went red — by a few percentages.

Here’s an electoral map from 2016.

(Gage, copyright permitted, without change, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/).

Four years later, the same swing states are in play.

As is enthusiasm. Unlike four years ago, both candidates have appealed to their base — COVID issues aside, it has been astounding the numbers to-date in mail-in votes and anticipated voter participation.

A good thing.

A voter can be passionate or indifferent on this election, enthusiastic or uncaring on a candidate, optimistic or pessimistic on government, or many shades in between, but, regardless of position, take a deep breath in advance of election day.

Know this: your vote is part of a grander plan, a greater scheme, and one important piece to the puzzle.

See you on Tuesday, November 3 — Election Day.

Jacques C. Condon, Marquette 1999, is owner of Condon Law Firm, LLC, in Thiensville, handling civil litigation, business law, and problem-solving cases ranging on everything from sports and entertainment to local-level government action.