Part Six: ELECTION LAW — Teachings of Elections Past

Teachings of Elections Past is your cocktail party discussion. This post provides context to CNN and Foxnews. It provides historical education on election day results. Election law teachings of elections. Part six, with this and other posts raising issues worth considering in advance of the upcoming Presidential election.

MAPPING FOR COLOR

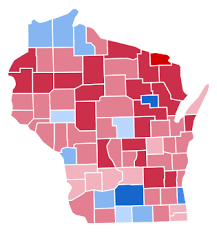

In the run-up to Election Day, maps of the United States will be colored as red or blue. This so-called “electoral map” is all the debate, particularly for the presidency, with pundits asking what color the “swing states” will shade.

The maps don’t show green, purple. There are only two colors, red or blue, sometimes tinted. Here is what the Wisconsin election map looked like after the 2016 presidential election.

(Photo credit Ali Zifan, without change, copyright permitted, license link https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/)

So why only two colors.

Without getting too far in the weeds, as it were, and from a political science view, the shading is based on the “winner-takes-all” principle.

One party wins and everyone else loses.

When a party loses, that party is without representation. Weaker parties are pressured to join a more dominant party in hopes of gaining a voice.

This leads to party-dominance.

Voters also learn that, because of party dominance, voting for a third party candidate is ineffectual to the result, further aligning into a two-party race between winners and losers.

And, in terms of the presidency, by devising a system of “electors” as opposed to popular vote, history teaches us that an indirect electoral-election scheme can lead to odd results.

ODD MAPS

The elections of 1876, 1888, 2000 and 2016 produced an electoral college winner who did not receive at least a plurality of the nationwide popular vote.

What did this mean? It means that in 2000, Al Gore received 543,895 more popular votes than George Bush, yet lost the election. The same was true for Samuel J. Tilden (New York) losing to Rutherford B. Hayes in 1876, and Grover Cleveland (New York), the incumbent President, losing to Benjamin Harrison (Indiana) in 1888.

The same was true in 2016 where Hillary Clinton outdid Donald Trump in the overall vote, yet lost rather handily in the electoral college vote.

My last post discussed a tie-breaker, per the Twelfth Amendment. To win the election, the presidential candidate must receive an absolute majority of electoral votes (currently 270). Donald Trump or Joe Biden need to clear the 270 vote hurdle.

If no candidate receives a majority of electoral votes in the election, the election is determined by the House of Representatives.

A run-off vote for Vice President belongs to the Senate.

As to a run-off presidential vote, this has happened but only once since 1804.

In 1824.

THE 1824 RUNOFF

Consider what happened in 1824. In the years prior, the Democratic-Republican Party had won the last six consecutive presidential elections, but, come 1824, the party failed to agree on a candidate choice for president.

Splintering into four separate candidates, the equally splintered election results — perhaps inevitable — resulted in no-candidate achieving an electoral-majority in votes. The election then went to House of Representatives.

In a prior post I described the pre-Twelfth Amendment cabal that took place in the year 1800 when the House, having a decision to make on the presidency, tied on 35 consecutive voting ballots. Thomas Jefferson won on ballot number 36. The Twelfth Amendment, as ratified in 1804, was an attempt to change this.

Twenty years after the Twelfth Amendment became law of the land, the election of 1824 put the Constitution into action.

Andrew Jackson obtained the majority of the minority of electoral votes, meaning he had the most electoral votes yet had not obtained the majority of electoral votes to become President.

Would the House vote the leading vote-getter into office? No.

Under the guise of party politics (and part of a much larger and contentious discussion that I will not get into), the House of Representatives voted and chose John Quincy Adams as the President.

Jackson’s folks called this the “Bad Bargain”. He would be elected President four years later.

While the odds of a tie-election would seem somewhat rare, watch-out Wisconsin! If voting follows old patterns, a Trump-electoral win in Wisconsin combined with a Biden-electoral wins in Michigan and Pennsylvania could result in, gulp, a tie.

ROSS PEROT’S OWN MAP

Which brings in Ross Perot.

In the 1992 election, Perot ran as an independent against the two-dominant party candidates, George H.W. Bush (the incumbent President and Republican Party candidate) and William Jefferson Clinton (the Democratic Party candidate). The election result showed Clinton winning big, at least in terms of electoral votes. Clinton carried 32 states, receiving 370 electoral votes. Bush carried 18 states, receiving 168 electoral votes. Perot did not carry a single state, and received no electoral votes.

Digging deeper into the 1992 election, however, is where the rub begins.

Clinton’s popular vote was just shy of 45 million, with Bush and Perot receiving over 39 million and 19 million votes, respectively. In election parlance, this meant that Perot’s popularity stretched across the county but he was not particularly strong in any one state.

Whether votes for Perot were votes that would have been for Bush is the political-debate; the same debate, with different players, has been played out through many recent elections.

(For election background, the Federal Register website, www.archives.gov/federal-register/electoral-college/ explains the above concepts in more detail.)

This election cycle is no different. To be sure, neither of the major party candidates have majority approval amongst all-voters, non-major candidates have a percentage of voter-approved popularity, and poll results, predicting the percentage divide, adjust daily.

THE 2020 MAP DIVIDE

What we do know is that, using history as a guide to this year’s election, the popular vote will be relatively close between the dominant parties.

It was close in 2016. It will be close again.

History tells us that the electoral vote may not follow the popular vote.

We also know that, in theory, a multi-candidate race where candidates have strong regional appeal, as in 1824, makes it quite possible that no party will obtain an electoral majority.

But applying this theory to today’s election cycle is complicated, and the odds of a splinter candidate having broad regional appeal such as in 1824 — which, it should be noted, would culminate in the Civil War a few decades later — is statistically slim, and unlikely.

ELECTORAL COLLEGE MAPS

Like it or not, the 2020 result may or may not be the overall popular choice among voters.

Such an “odd” result has not sat well with Congress.

According to the Office of the Federal Register’s online materials, reference sources indicate that over the past 200 years, over 700 proposals have been introduced in Congress to reform or eliminate the Electoral College, and there have been more proposals for Constitutional amendments on changing the Electoral College than on any other subject.

The larger question is whether a change to the electoral system, or the election law as it now exists, is needed.

Or, as I would frame the issue, is the 2020 election cycle, with the possibility of an odd-result and an unpopular President-elect, really what the framers intended in 1787 when drafting the Constitution of the United States?

And on this question you’ll have to view my next and final post “Election Debate”.

Jacques C. Condon, Marquette 1999, is owner of Condon Law Firm, LLC, in Thiensville, handling civil litigation, business law, and problem-solving cases ranging on everything from sports and entertainment to local-level government action.